The employees of the Polish Red Cross carried out the exhumation of Polish officers murdered in the Katyn Forest while also being responsible for creating the official Katyn Lists.

After the Red Army entered Polish territory, thousands of Polish military personnel and representatives of the intelligentsia fell into Soviet captivity. The NKVD placed them in special camps, previously organizing a selection for officers, non-commissioned officers, and privates. The latter were handed over to the Nazis and sent to Germany for forced labor. The officers ended up in camps in Kozielsk, Starobielsk, and Ostaszków.

The decision to exterminate the Polish prisoners held in NKVD camps and prisons was made at the highest levels of Soviet power. The primary advocate for the approval was Lavrentiy Beria, the commissioner for internal affairs of the USSR, and the request was signed by Joseph Stalin himself. The prisoners were transported in batches to execution sites: from Kozielsk to the Katyn Forest, from Starobielsk to the NKVD prison in Kharkiv, and from Ostaszków to the NKVD prison in Kalinin. The victims of the Katyn massacre included 21,587 Polish citizens – prisoners: 4,421 from Kozielsk, 3,820 from Starobielsk, and 6,311 from Ostaszków, as well as 7,305 prisoners held in prisons in the western regions of Soviet Ukraine and Belarus.

“Like thunder from a clear sky, the news of the crimes committed in Katyn fell upon us […] thousands of families plunged into mourning and bottomless despair,” wrote Maria Tarnowska.

In this difficult situation, the Polish Underground State ordered the acceptance of a German invitation for the Polish Red Cross to participate in the exhumations and identifications of the bodies, but on the condition that it would take place under conditions ensuring the possibility of an objective judgment. The task of the Red Cross was to establish the factual state of affairs, without accommodating German propaganda. The Germans at that time ultimately decided to transfer the exhumation in the Katyn Forest to the Polish Red Cross. Fearing its refusal, they used – as in many other cases – deception. On the morning of April 14, Dr. Grundmann personally appeared at the PCK headquarters and conveyed an oral order to President Lachert for a 5-member PCK delegation to travel to Smolensk, simultaneously informing that on the same flight from Krakow were the PCK representative for the Krakow District Stanisław Plappert and his deputy Dr. Adam Schebesta, as well as delegates from Cardinal Adam Sapieha's representatives from the clergy. In case of refusal, reprisals were threatened. "The Presidium of the Central Board decided to send five people from Warsaw to Smolensk, namely the Technical Committee consisting of four members, which in case of need would remain on site, as well as the Secretary – a member of the Central Board, Mr. Skarżyński (…)".

In the instruction given to the members of the PCK Committee, the Presidium of the Central Board categorically emphasized that only Kazimierz Skarżyński could act on behalf of the PCK. In a short time, a “skeleton” of the Technical Committee had to be chosen – in case of possible work in Katyn – this team was to be reinforced. Director Gorczycki assigned officials from the PCK headquarters and the Warsaw District to it: Captain Ludwik Rojkiewicz – as the manager, in addition Jerzy Wodzinowski and Stefan Kołodziejski, physician Dr. Hieronim Bartoszewski (the sanitary chief's deputy for the Warsaw District PCK) and driver Adam Godzik – a physical worker. They all, as Kazimierz Skarżyński wrote:“agreed to altruistically leave for Katyn immediately.”Members of the Technical Committee received personally addressed letters with the following content: “The Central Board of the Polish Red Cross delegates you based on the resolution cited below to Smolensk, in the capacity of a member of the Technical Committee (…)”. In the Krakow group, apart from Plappert and Schebesta, there were: Reverend Stanisław Jasiński and Dr. Tadeusz Susz – Pragłowski – criminologist, senior assistant at the State Institute of Forensic Medicine and Criminology in Krakow. “Upon departure, Kazimierz Skarżyński wrote – and throughout the entire stay, we were formally surrounded by cameras and film equipment, constituting a real plague, from which one literally could not escape”. He issued a special order to the members of the PCK to stay together, avoid forming common groups with the Germans, especially when photographing, not to sit with them at the table, and not to engage in any unnecessary conversations. This was intended to avoid the appearance of cooperation between the PCK and the Germans. In Smolensk, they were accommodated in a military hotel.

On April 16, 1943, at dawn, Rev. Canon Jasiński held a mass in the chapel of the military hospital in Smolensk in remembrance of the Polish officers murdered in Katyn. Then, after two days of delay, the PCK group was taken to the Katyn Forest. As they later learned by chance, this delay aimed to extract a greater number of bodies from the mass graves – for a stronger effect. Dr. Schebesta felt there was almost a theatrical preparation for the arrival of the Poles at the collective gravesite. “Around were set up towers for the cameramen, masts with Red Cross flags, microphones were hung, and cables laid. “We stood – Skarżyński wrote – as if petrified. On the grass and moss around us lay approximately 400 already excavated bodies, and beyond the large grave, we saw outlines of others. Like in a dream, I moved forward. It took several minutes before I calmed down and remembered that concrete tasks were facing me. There was no doubt that we were dealing with a mass execution carried out by experienced executioners. […] Polish uniforms, insignias, decorations, regiment insignia, coats, pants, and shoes were well preserved, despite contact with the ground and decay. In the depths of the excavated deep pits were further layers of corpses, and skulls, legs, arms, or backs were protruding from the tightly packed earth […]”.

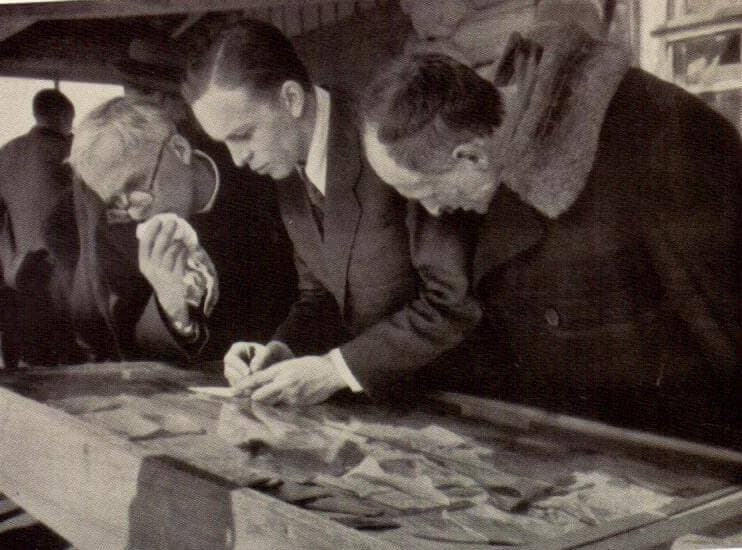

“Father Jasiński, ghastly pale and near fainting, put on liturgical vestments and, praying for the dead, sprinkled holy water over the graves and sprinkled them with soil brought from Poland. We knelt and recited prayers with him while the Germans and a group of Russians watched us in silence. Immediately after fulfilling his duty, the priest stood up but immediately fell, fainted” – Skarżyński wrote further. No one who saw the Katyn Forest in the spring of 1943 could free themselves from that sight for the rest of their lives. Kazimierz Skarżyński's daughter recalled how – already in Canada – her father once spoke about Katyn at dinner and was so moved that he began to choke and could not produce a sound from his constricted throat. From the Katyn forest, the Poles were taken to the GFP office located a few kilometers away, where inspections of documents found with the bodies were conducted and a small exhibition was organized. In Katyn, for now, three members of the Technical Committee remained (Rojkiewicz, Wodzinowski, Kołodziejski). The remaining PCK delegation returned to Warsaw and Krakow. On April 17, 1943, Skarżyński submitted a report to the Presidium of the Central Board of the PCK, after which it was stated that the German authorities in the GG were informed that the PCK was ready to begin work in Katyn and awaited their written authorization. It is worth emphasizing that the Germans were solely interested in propaganda, while the PCK sought professional exhumations and the swift burial of the victims' bodies. One example of German pressure was the issuance of a brochure about the Katyn massacre, the draft of which was handed to President Lachert with a demand to write an introduction for it. It was to appear in large print, to be spread by PCK facilities, and the proceeds from its sale were to support the PCK's account. Despite the very difficult financial situation, the Central Board again resisted this proposal, firmly opposing the printing of any information regarding the PCK's association with that publication on the cover.

The exhumation was started on March 29, 1943, by Professor Buhtz with his team consisting of: 3 forensic doctors, 2 forensic chemists, 3 preparators, and sectional assistants, 2 photo lab technicians. The three-member PCK Technical Committee commenced work on April 17, 1943. By then (over three weeks), the Germans had exhumed about 300 bodies from the graves and included them on the exhumation lists – they lay unburied. In selecting further members of the Technical Committee, physical endurance under the conditions of constant presence in contaminated air close to decaying bodies had to be taken into account. On April 19, 1943, Hugon Kassur, Gracjan Jaworowski, and Adam Godzik from the Central Board and the Warsaw District of the PCK arrived in Katyn. On April 28, the last group of Poles arrived: Stefan Cupryjak and Jan Mikołajczyk – officials from the Central Board of the PCK, as well as Dr. Marian Wodziński, senior assistant from the State Institute of Forensic Medicine and Criminology and his three sectional assistants: Władysław Buczak, Franciszek Król, and Ferdynand Płonka. From the departure of Kassur until the end of the exhumation, they worked in a 9-member composition.

It should be noted that the Technical Committee had very modest equipment, which could not be supplemented by a shipment from the country. The lack of rubber gloves (only 13 pairs were taken) and rubber boots (only one pair was available) was particularly felt. The Poles were accommodated until May 20 in a separate barrack in the village of Katyn, and afterwards in a local school near the Katyn station. The results of the exhumations were awaited with tension by the Poles, especially the families of the victims. The most complete report describing the activities of the Technical Committee in the Katyn Forest was prepared by Kazimierz Skarżyński in June 1943 – almost immediately after the completion of the exhumation. It was: A confidential report on the entirety of the Polish Red Cross's participation in exhumation works in Katyn near Smolensk for the period of April – June 1943, submitted at the request of the Central Board by the Secretary General of the Polish Red Cross – consisting of 60 pages.The scope of work conducted by the PCK Technical Committee included: exhuming bodies from the original graves, searching the bodies and marking them with consecutive numbers, examining the bodies and determining the causes of death, burying the bodies in new brotherly graves, and identifying the bodies based on found documents and items.

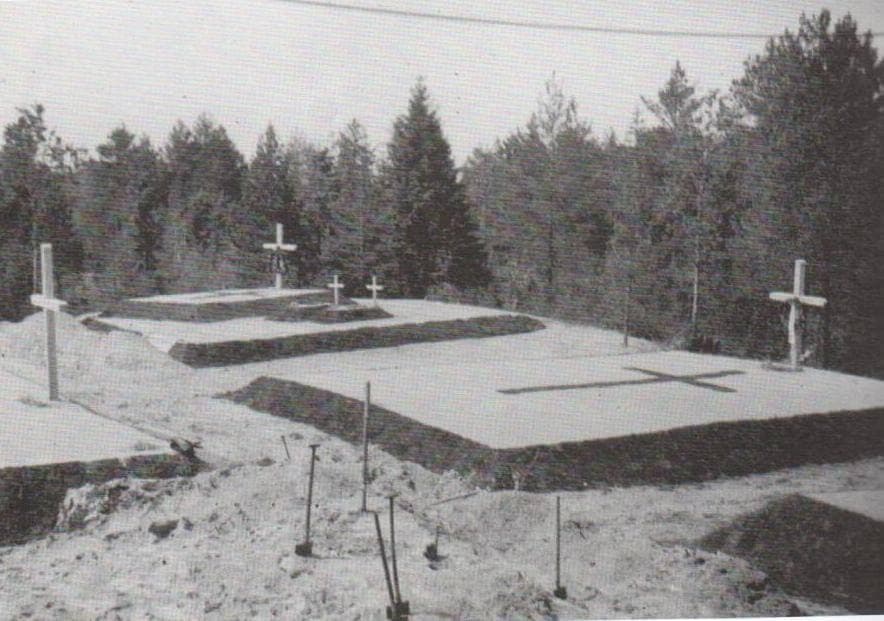

In the spring of 1943, a total of 4,243 Polish officers’ bodies were exhumed in the Katyn Forest. It is worth emphasizing that all KT activities took place under constant supervision of GFP officials. The work of the 9-member group of Poles was carried out for many hours a day (generally 10 hours with a 1.5-hour lunch break) in the dreadful stench emanating from open graves and unburied bodies. Work on the so-called PCK cemetery consisting of 6 flat brotherly graves, in which 4,241 Polish officers were laid to rest, continued until June 7. Major generals were buried in separate graves. Each grave was marked with a 2.5-meter wooden cross; on the highest one hung a wreath made by the Poles from metal and wire with a thorny crown of barbed wire inside and an eagle taken from an officer’s cap nailed to the cross. After the exhumation, the Katyn case at the Central Board of the PCK concentrated on examining the documentation found with the bodies, preparing, as much as possible, a complete list of exhumed persons, and issuing death certificates to the victims' families.

Letters sent from Katyn to the Central Board of the PCK regarding the exhumed were primarily immediately and accurately copied in the Information Office, with each page of the copy being signed by the person verifying its accuracy against the original and stamped by the PCK Information Office. The contentious issue between the Central Board of the PCK and the Germans concerned the so-called Katyn legacy, i.e., documents and items found with the murdered. The GG authorities decided to transfer them for further examination to the State Institute of Forensic Medicine and Criminology, led by German Dr. Werner Beck. The first box of Katyn deposits was brought to the country on May 12, 1943 – it contained 376 envelopes, ending up in the Chemical Department of the Institute in Krakow. It was headed by Dr. Jan Zygmunt Robel, and staffed by Poles. As Skarżyński wrote, these deposits: “For the Polish nation represented an invaluable treasure, both emotionally and historically”. All materials from Katyn were delivered to the Chemical Department on June 28, 1943, through the Main Department of Propaganda of the GG government. It consisted of 9 large wooden boxes and one small one, containing documentation designated by the Germans for a planned mobile Katyn exhibition. Dr. Robel’s team worked on the Katyn documentation in strict and constant contact with the PCK Central Board in Warsaw and the management of the Krakow District of the PCK.

Saving the Katyn documentation

The Poles feared that the Germans would transport the boxes to the west, which is why the PCK, together with the AK, took intense actions to take over the Katyn documentation. From the PCK's side, Dr. Schebesta was primarily involved in this matter. Boxes lined with zinc inside were prepared, into which the Katyn envelopes were to be transferred; after being sealed, they planned to sink them in a chosen pond. With the help of Dr. Robel, Schebesta managed to bring the boxes into the Institute of Forensic Medicine, but at that time the Germans ordered the immediate transfer of materials from the Chemical Department's premises to the Institute building at Grzegórzecka 16. In all post-war accounts and testimonies on this subject, there is mention of the “indiscretion” of one of the physical workers of the Institute, through which the Germans learned of the plans to take over the documentation. On August 4, 1944, the boxes with the Katyn deposits were transported by Dr. Beck to the Institute of Forensic Medicine at the University of Wrocław and some time before the city was surrounded by the Red Army, in early February 1945, transferred to Radebeul near Dresden and stored in a railway warehouse. Before the entry of Soviet troops, according to an order issued for such an occasion by Beck, the boxes were burned. Whether this actually happened – we do not know.

On August 2, 1944, the archive of the PCK Central Board burned down along with the entire building, set on fire intentionally by the Germans. According to Kazimierz Skarżyński, the secret PCK archive with materials regarding Katyn also burned at that time. However, in 1989, hidden copies of exhumation letters sent between May and July 1943 from the PCK Central Board were found in the attic of the building of the Provincial Board of the PCK in Lublin. These were – until 2011 – the only known Polish letters from the exhumations in Katyn. However, Rev. Prelate Stefan Wysocki in 2011 transferred to the Archive of New Acts documents regarding Katyn received in 1977 from the former head of Department I of the PCK Information Office, Jadwiga Majchrzycka, who kept them in the secret compartment of her apartment. It remains a mystery how and from whom she received these documents. It is known that she was a soldier of the AK, participated in the Warsaw Uprising – after its fall she found herself in Krakow as the head of the PCK Information Office branch, returning to Warsaw and its archives in March 1945. Regardless of how she took part of the Katyn documentation, it should be emphasized that she demonstrated extraordinary courage, almost heroism by preserving the materials for 30 years, caring for their rescue even on her deathbed.

Katyn boxes

The topic of the Katyn boxes containing various memorabilia of the murdered officers has been repeated for many years. It is worth noting the memories of Kazimierz Skarżyński’s family, who claimed that one of the boxes was secured in a metal case and hidden in a lake.

After many years, in Krakow, the topic of the Katyn box was mentioned by opposition activist in the PRL and AGH professor Jan Sentek. His account was recorded in 1991 by Adam Macedoński, creator of the Katyn Institute. The professor described an unknown operation organized by AK soldiers, whose goal was to obtain items from Katyn brought by the Nazis. Employees of the Krakow branch of the Polish Red Cross were said to have participated in their concealment.

In connection with Professor Jan Sentek's account, the Institute of National Remembrance decided to initiate a search investigation. At their request, scientists from the AGH partially examined using ground-penetrating radar the courtyard of the building of the Małopolska District of the Polish Red Cross, but in the first stage, the examination did not yield positive results.

However, in order to consider the investigations correct and complete, they should be carried out using deeper-reaching equipment. In the course of collecting various kinds of information, the Małopolska District of the Polish Red Cross obtained information that in the 1980s or 1990s, an additional 1.5 to 2 meters of earth and rubble had been brought to the courtyard, which additionally hinders the investigation. The presence of a rock garden located in this area as well as a buried well is also problematic. Moreover, a large room currently used by MOO PCK rescuers as a storage room used to be a wooden shed. Due to the massive number of items, this area was examined only in two places, while the metal room located in the corner of the garden was not checked in any way because of too much interference due to the material from which it was made.

MOO PCK is currently preparing to conduct further searches both in the garden area and in all cellars located within the building, expressing its willingness to conduct geological as well as archaeological research on the premises of the Krakow District, and has declared all assistance in conducting them, making available the internal garden, courtyard, and cellars – agreeing to the readiness to disturb the earth and the architecture of the garden.

Everything, and even much more than could have been done in these conditions for the Polish officers and their families – has been accomplished. Skarżyński stated: “One thing is certain: from the institutions that worked on the case, only the PCK cannot be accused of bias. […] Only the PCK, along with Professor Robel’s team of criminologists in Krakow, investigated the case really comprehensively, diligently, with a two-month exhumation effort on site and a year-long scientific examination of documents in Krakow. Only they were driven by the pure Red Cross idea of ignoring enemies and serving the truth.”

It is worth emphasizing that the participation of the members of the PCK Technical Committee in the Katyn exhumations affected their entire lives. Interrogations, persecutions, arrests, and escape from the country were the reality encountered by these Red Cross heroes.

Moreover, in June 1991, a decision was made to send Polish experts to Kharkiv, Katyn, and Miednoje, who participated in the exhumations of the officers. They were conducted in 1991 and in 1994 and 1995. Representatives of the Polish Red Cross participated again in all of them.

Thus, regarding those events speaks one of the participants in the exhumation, Ms. Elżbieta Rejf – head of the Information and Search Office of the Central Board of the PCK: “The Katyn case is a very painful chapter in the work of the Polish Red Cross. After the war, families of officers and soldiers of the WP taken captive in September 1939 addressed themselves to the Information and Search Office of the PCK. Unfortunately, despite the efforts made, we were unable to obtain confirmation of their fates. Being able as a PCK representative to take part in the exhumation of a prosecutorial-investigative character was a great honor for me and our institution. It was after 48 years since the discovery in the Katyn forest of the bodies of murdered Polish prisoners of war. The work of the Office began on July 25, 1991, in Kharkiv, and after 2 weeks in Miednoje. No words can convey what we saw upon the discovery of the death pits. Shot skulls and bones, among them uniforms, caps with hidden medals of dedication, badges, fragments of letters from loved ones. Although there were moments of breakdown, they lasted briefly. We were very keen to recover as many human remains and items found with the bodies as possible within the specified time frame. The families in Poland were waiting for this information. I continued my work during the next exhumation in 1995 in Miednoje.”

On April 18, 2004, ROPWiM (the Council for the Protection of Memory of Struggle and Martyrdom) placed a plaque commemorating the members of the PCK Technical Committee who worked in Katyn in 1943, including its chairman Kazimierz Skarżyński, on the wall of the church of St. Charles Borromeo in Warsaw.

Facts about the Polish Red Cross

Only after the fourth request to the International Red Cross was the Polish Red Cross recognized on the international stage.

The beginnings of blood donation in the Red Cross date back to 1935, which took place 83 years ago.

If the borders of Poland had not been changed after World War II, the 100th anniversary of the Polish Red Cross (PCK) would have been celebrated with the Lviv, Volhynian, and Wilno branches, which are still active today but under the structures of different state associations.

The employees of the Polish Red Cross carried out the exhumation of Polish officers murdered in the Katyn Forest while also being responsible for creating the official Katyn Lists

The Red Cross movement and its foundations were the source for the establishment of sanitary services for wounded soldiers under the names Polish White Cross and Polish Green Cross.

Over the years, the rules for statutory financing of the PCK's activities have changed, as has our role and position within the state.

The PCK enjoyed immense public trust during the Second Polish Republic, and the most important figures in the state always spoke about our organization with the utmost respect.

To this day, in Tarnów, Małopolska, there is a nearly 100-year tradition of parades through the city organized on the occasion of the Polish Red Cross Week.

On February 8, 2018, it was 50 years since the establishment of the badge of the Honorable Blood Donor

On February 8, 2018, it marked 50 years since the establishment of the badge of the Meritorious Honorary Blood Donor

PCK never accepted any gratifications and did not support the Nazi authorities, thereby exposing itself to severe consequences.

The Polish Red Cross was the initiator of healthcare in rural areas during the interwar period and the establishment of the first village health centers.

PCK was involved in the construction of the Marshal Piłsudski Mound in Sowińca in Krakow in 1936

At the beginning of 1919, within the structures of the newly established Polish Red Cross Society, 3 District Branches of the PTCK were created: for Galicia, the Grand Duchy of Posen, and Silesia.

During its 100-year activity, the Polish Red Cross, the International Committee of the Red Cross, honored 102 Polish nurses associated with our organization with the Florence Nightingale Medal.

The Polish Red Cross was the organizer of parachuting courses

Did two Polish doctors working at the Red Cross hospital during World War II save more lives than Oskar Schindler?

There existed simultaneously the Polish Red Cross and the Polish White Cross, whose president was Helena Paderewska.

There was a time in the history of PCK when, legally, two or even three Main Boards of PCK operated simultaneously.

Help us endlessly

Thanks to the kindness and support of our Donors, we can help children, seniors, support medical rescuers, promote the idea of blood donation, and implement many other projects that save lives in times of conflict or humanitarian crises. Every donation and every form of support is significant because the Polish Red Cross connects those in need with those who want to provide help. Let’s help together!

See also

20. Gdyby granice Polski nie zostały zmienione po II wojnie światowej, to obchody 100-lecia PCK świętowały by z nami działające do dziś, ale w strukturach innych stowarzyszeń państwowych Oddziały Lwowski, Wołyński i Wileński

After the establishment of the Polish Red Cross Society, 4 large Regional Committees were created: Lesser Poland, Greater Poland, South-Eastern, and Polesie-Minsk, with main centers in Krakow, Lviv, Poznań, and Warsaw. The creation of these regions was recorded in the first Statute of the PTCK from 1919.

You are currently viewing a page filtered by content from the department. Cała PolskaIf you want to view content from Cała Polskaclick the button